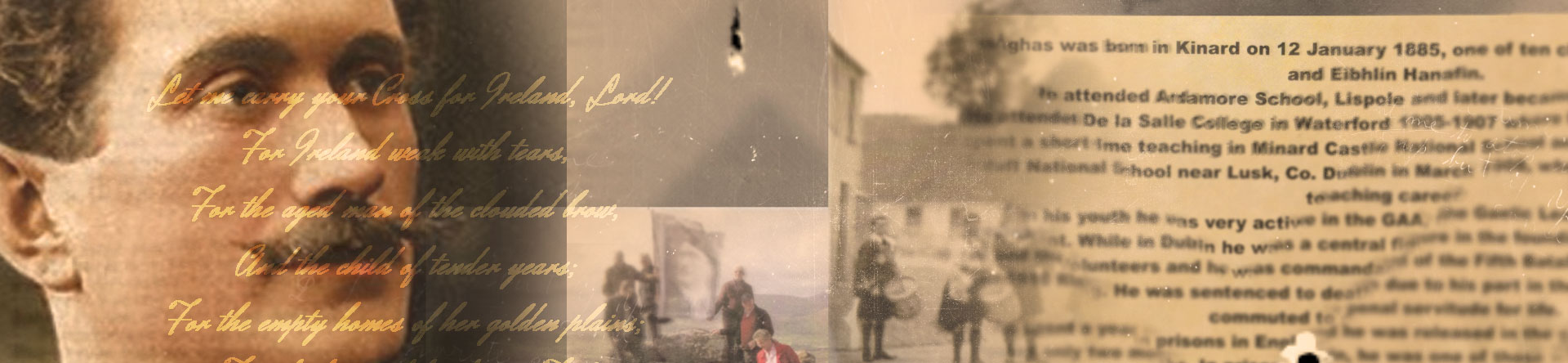

Thomas Patrick Ashe (12 January 1885 – 25 September 1917) was a member of the Gaelic League, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and a founding member of the Irish Volunteers

Thomas Ashe Audio Clips

Some audio remembrances of Thomas Ashe by Lusk Heritage Group

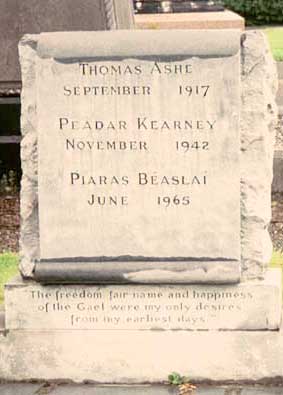

Ashe's Resting Place

Thomas Ashe’s Death

The death of Thomas Ashe and the subsequent funeral procession had a striking effect on the attitude of the Irish people and became a rallying call to the standard of the Irish Republic. Thomas Ashe’s remains lay in state in Dublin’s City Hall before a funeral procession of over 30,000 marched to Glasnevin Cemetery on 30 September 1917.

Michael Collins delivered the funeral eulogy in Irish and English, following the firing of a volley by uniformed Irish Volunteers. The English eulogy being ” nothing additional remains to be said. That volley which we have just heard is the only speech which is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian”.

Thomas Ashe Videos

SOME THOMAS ASHE RELATED VIDEOS FROM THE LUSK HERITAGE ARCHIVES

Tree Planting

Thomas Ashe

The Lusk Connection

Thomas Ashe

Inquest

Thomas Ashe

Corduff NS Tribute

Thomas Ashe

100 Years 1916-2016

Thomas Ashe

A Tribute

Thomas Ashe

The Inquest on the Death of

Thomas Ashe

FROM A SPEECH GIVEN BY AIDAN ARNOLD ON 26TH AUGUST, 2015

Tonight, I want to talk about an aspect of Thomas Ashe that is largely forgotten. Not about who he was, where he came from or what he did in 1916, but about the Inquest on the death of Thomas Ashe.

About 25 years ago while browsing through an old second hand bookshop I came across a booklet entitled The Death of Thomas Ashe, Full report of the inquest. It was published by J. M. Butler of 41 Amien Street in 1917. This was a word for word record of the eleven days of evidence given at the inquest on the death of Thomas Ashe.

I attended, as did my three beautiful daughters, Corduff National School where Thomas Ashe was headmaster from 1908 until 1916. I wrote a play entitled The Legacy of Ashbourne based on this detailed record of the inquest. Along with a group of parents we put in on to raise money for Corduff school. My speech tonight is based on that factual record.

The Case for Both Sides

The state’s case was that Thomas Ashe was serving a two-year prison service for sedition arising out of speeches he made in 1917. He refused to obey prison rules, with other prisoners he took part in a prison riot breaking glass in the cells and damaging furniture before going on hunger strike. The Prison authorities were forced to act to maintain order. They had to force feed him to protect his life but unfortunately, he died in the process. What happened to him was self-inflicted arising from his own actions.

The case for the Ashe family was Thomas Ashe and the other prisoners had demanded to be treated as political prisoners and not criminals. To break their spirits the prison authorities had illegally removed the prisoners’ bed, bedding and boots from their cells. Their hunger strike had been sparked by this illegal action. There was no riot, the only glass broken in the cells was the spyholes in the doors so prisoners could call out to each other. The force feeding was brutally enforced and Ashe had actually choked to death as a result.

The witnesses included the Lord Mayor of Dublin who had intervened to help the prisoners and to stop the prisoners from being maltreated, the chairman of the prison board Max Green was called but refused to answer any questions, claiming what he calls Privilege after every question. Various doctors were called in evidence. Most gave fair and balanced testimony but Dr William Henry Lowe, who had administered forcible feeding, was a particularly unconvincing witness.

The best way I can in a given an accurate account of the proceedings is to quote the summaries which were delivered at the end of the eleven days’ inquest by both sides. Ashe’s next of kin was represented by Timothy Michael Healy who was an experienced politician and legal expert. He had been a member of Parnell’s Nationalist Party He was first up Healy’s summary for Ashe’s next of kin.

We have been investigating the death of a very unusual man, a death so tragic and a man so remarkable, that as we know his coffin was followed by 100,000 people. No words of mine are needed to stress the importance of this inquest or of your verdict. Throughout, the prison authorities have not uttered one word of regret for the conduct of those who brought Thomas Ashe to his death. In fact, their attitude could be summed up by a phrase Mr Hanna used when he said “If he felt the cold he has himself to blame for it. “

What was the prison authority’s case? They say that the deceased was the architect of his own misfortune, that he was treated with absolute legality in the prison and that everything flowed from his own misconduct, from his own lawlessness and from his breach of the prison rules.

That case, which my learned friend Mr Hanna has presented, is, I say now without apology, as false as hell itself. There is not one word, one shadow or tittle of foundation in it. That case has been deliberately and disgracefully concocted by the prison board to escape guilt of wilful murder which lies at their door.

What really happened? Thomas Ashe started his sentence on September 11th. Immediately he refused to work or obey prison rules. He was punished by being deprived of books and losing remission on his sentence. From then until the day he died, no other punishment according to the Deputy Governor was ever inflicted on him.

Yet the Lord Mayor of Dublin has told us that he found Mr Ashe in a naked cell, having lain there for two days and two nights without bed, bedding or boots and racked from want of sleep. Do you know, gentlemen, what Thomas Ashe said to the Lord Mayor? I’ll tell you. He said simply “I don’t know what I have done to deserve this treatment.”

Ashe had been found guilty of an offence and was being punished for it. But this was in addition to that, this was illegal and unrecorded. The prison authorities had been caught in the act, whoever was responsible had to make up an excuse for it, and then they put the cart before the horse.

They invented the story of the smashing of the glass and the furniture, of the pandemonium. Then of the Deputy Governor driven to interfere, and all after the prisoners had committed illegalities and commenced a hunger strike, as it was stated, without provocation.

At that stage, there was no thought of a hunger strike. True, the prisoners planned a hunger strike on October 1st if their demands for a different status were not met. But this was September 20th, eleven days earlier, when the cells were stripped. It was this order from the Prison Board which sparked off the hunger strike there and then. That order from Mr Max Green, the Chairman of the Prison board, is what brought Thomas Ashe to his grave. If it were not for the intervention of the Lord Mayor, we could have forty corpses in Mount Joy Prison instead of one.

Green’s strategy was simple: not to concede the demands of the prisoners but instead to gamble his cruelties against their courage. Mr Max Green thought he would break Ashe’s spirit, but he only succeeded in breaking his heart.

I strongly object to the attitude which the prison authorities have adopted to this whole inquest. The jury are entitled to the fullest information in this case, not partial information, not partisan information, nor political information. At the beginning of this inquest the only people who knew all the facts surrounding the death of Thomas Ashe were the prison authorities and officials. We would have expected honesty or some sign of regret from them for this tragic affair. So, what did we get? As soon as they thought we were getting uncomfortably near the truth, they threw their shield of privilege around them. What is this Privilege? The privilege to conceal responsibility. The privilege to hide the guilty. I would submit that the invention of the doctrine of privilege in matters of life and death such as these, cannot and should not exist. At this stage, despite all the authority’s efforts, nobody can be in any doubt as to the degrading treatment Mr Ashe was subjected to before and during his hunger strike. I see no point in going into the terrible details again.

What have they achieved in Dublin Castle? Nothing, absolutely nothing. The prisoners’ original demands are now conceded in full, Thomas Ashe is dead. Other nations will read about it, in times to come. They will be heartened by the story of this humble, uncomplaining schoolmaster, who stood up against tyranny. But it is for you the jury here and now to appraise the blame as to how this man met his untimely end. It is for you to so frame your verdict that people may know that this man was no suicide. Thomas Ashe loved life, and that life was brutally taken away from him. If you find in accordance with those facts then his death will not have been a complete waste. Others have tried to avoid their responsibilities, I trust you will not avoid yours. I leave that in your hands gentlemen!

The state was represented by Henry Hanna KC. He was a lawyer of distinction who would later become a High Court judge.

Hanna’s Summary for the State

At the outset, I must object to Mr Healy’s conduct throughout this inquest. All during this case he has used extremely violent and unnecessarily abusive language. He has shown complete recklessness in the statements he has made and has disregarded every canon of decency on his examination and cross-examination of witnesses. His conduct has been unparalled in the history of the Irish Bar.

The result of his attack on Dr Lowe and Mr Max Green was that Dr Lowe is practically ruined in his profession, and both he and Mr Green are under constant police protection.

I would ask the jury to leave out of their minds all the frenzied wild statements which have been made and deal only with the facts of the case. I put it to you – do you believe if Thomas Ashe had taken the food offered to him from the time he went into prison, that he would be dead today? He would not.

The law states that when a prisoner refuses food, the jailor is obliged to preserve his life. It is, I submit, irrelevant to the inquiry whether artificial feeding is morally right or wrong. The law is that artificial feeding was necessary and you, the jury, should start off with that proposition in mind.

There is absolutely no doubt that there was a concerted effort among all the prisoners to defy the rules in Mountjoy Prison. They were faced with what could only be called a mutiny. Mr Healy tells us what Thomas Ashe is supposed to have said to the Lord Mayor. Do you know what his last words were to his priest? He said “Father, we made a great fight.” A great fight! Mr Boland was up against very resolute and determined men. What would have been said if he had given in to that, if he had not been able to govern his own prison. He had to act!

Thomas Ashe did not catch cold and he did not complain of having caught cold. Much has been made of this matter of his bed and bedding while referring to the causes of death. At no time did Ashe complain of being deprived of his bed and bedding.

All the doctors gave their evidence voluntarily and openly and all have agreed that the cause of death was heart failure following congestion of the lungs. There is not a shred of evidence despite Mr Healy’s insinuations, that Dr Lowe or anyone else was negligent in anything they did.

Mr Ashe seems almost to have contemplated death. I would not go so far as to say that he committed suicide, that is a word which Mr Healy has bandied about, but he certainly was well aware of his situation. Think back to what he said to the Lord Mayor about that. He said “If I die, I die in a good cause.”

Mr Ashe was a very determined man. He made his fight, and in doing so, he sacrificed his life. It is for you the jury to say how far his own actions contributed to that. The fact is if Thomas Ashe had taken his food he would be alive.

The Verdict

We find that the deceased Thomas Ashe, according to the medical evidence of Professor McWeeney, Sir Arthur Chase and Sir Thomas Myles, died of heart failure and congestion of the lungs on September 25th and that his death was caused by the punishment of taking away his bed, bedding and boots, and being left to lie on the cold floor for fifty hours, and then being subjected to forcible feeding in his weak condition after a hunger strike of five or six days.

We censure the castle authorities for not having acted promptly, especially when the grave condition of the deceased and other prisoners was brought to their notice on the previous Saturday by the Lord Mayor and Sir John Irwin; and find that the hunger strike was adopted against their being treated as criminals after they demanded to be treated as political prisoners. We condemn forcible or mechanical feeding as an inhuman and dangerous operation and say it should be discontinued.

We find that the assistant doctor who was called in, Dr Henry Lowe, having had no previous practise in such operations, administered forcible feeding unskilfully; and that the taking away of the deceased bed, bedding and boots was an unfeeling and barbarous act.

And we censure the Deputy Governor for violating the prison rules and inflicting punishment which he had no power to do. We infer that he was acting under instructions from the Prison Board at the Castle, which refused to give evidence and documents asked for.

We tender our sympathy to the relatives of the deceased in this sad and tragic occurrence

AIDAN ARNOLD, 26TH AUGUST, 2015

Thomas Ashe

The Fingal Years

AIDAN ARNOLD 7TH MARCH 2017

I want to take this opportunity today to salute a not forgotten but sometimes underestimated hero of 1916, a native son of Kerry and an adopted son of Fingal. Although Thomas Ashe is rightly remembered as a Kerry born Irish Nationalist, the Ashe (originally D’Esse) family came from France at the time of the Norman Conquest and settled in Devon. From there they crossed over to Ireland to Kildare in the 12th century. In the late 1600s or early 1700s their extensive lands were confiscated because they refused to renounce their Catholic faith. One of the family was hanged for rebellion during this period. Most of family moved to Kerry and many generations later Gregory and Ellen Ashe had 10 children there of which Thomas was the sixth. The famous American actor Gregory Peck was a cousin of Thomas Ashe.

When Thomas Ashe moved from his beloved Kinard and took up the position of principle of Corduff National School in Lusk, North County Dublin, in March of 1908 at the remarkably young age of 23, surprisingly he was not flying that far away from the family nest.

My own grandparents arrived in Corduff about six years earlier in 1902. I was born there in 1950, I grew up less than one hundred yards from Corduff School. When I married in 1976 I moved that hundred yards to face the school and bring up my own family looking directly across at the school and the house that Thomas Ashe lived in for his eight years in Fingal. I attended Corduff national school as have two further generations of my family since then.

When I first entered Corduff School in 1955 Mary Monks or Miss Monks as she was respectfully addressed in those years, was a living link to Thomas Ashe and the Easter rising. She thought with Ashe up until 1916 as a junior teacher. My abiding memory is of a lively white haired teacher who was friendly but also knew how to control a class. One odd memory is the shock I got at receiving my first slap across the knuckles with a wooden ruler when I did a subtraction sum back-to-front probably at about the age of six. In those years Corduff was a two teacher, two room school and I was still in Miss Monk’s room when I got that rude awakening. Of course corporal punishment was still allowed in schools in the 1950s but Corduff practised it very sparingly . The worst I can remember the head teacher Ned Dunne doing was to lose his patience at regular enough intervals, throw a piece of chalk at a pupil and shout “I wish it was a brick.”

Thomas Ashe’s house adjoining Corduff School became a meeting place for many of the leading politicians, sporting and literary figures of the time. Among the regular visitors to his home were Maud Gonne, Sean O’Casey, Eamon De Valera and Michael Collins. After one rather spirited meeting one of those present jumped on a chair and wrote over the front door. “Liberty Hall” The significance of the name was unmistakable.

The original Liberty Hall in Dublin stood on Beresford Place and Eden Quay, near the Custom House. It started out as a hotel before it became headquarters to the Irish Citizen Army. During the 1913 Dublin Lock-out a soup kitchen for workers’ families was run there by Maud Gonne and Constance Markievicz. Following the outbreak of the First World War a banner reading “We Serve Neither King nor Kaiser, But Ireland” was hung on its front wall. The Irish Worker newspaper founded by Jim Larkin operated from Liberty Hall from 1911 to 1914. James Connolly edited the paper when Larkin was in jail during the 1913 Dublin Lock-out. The newspaper was shut down in 1914 by the British government, for sedition under the Defence of the Realm Act, the same law that three years later after the failed Easter Rising was used to re-arrest Thomas Ashe and that ultimately led to his death. The Irish Worker was replaced for a short time by a paper called The Worker until that too was banned. Connolly edited a third paper, The Workers’ Republic, from 1915 until the Easter Rising in 1916.

In all likelihood Ashe received his solid grounding in social consciousness and his unwavering moral compass from his early years growing up in Kinard in Kerry, under the guiding principles of his parents Gregory and Ellen Ashe. The oral traditions of the seanachai as practised by his father and shared with other natural story tellers and local historians around the kitchen fire, reaching back to stories of the famine in the 1840s, was an ever present part of his formative years. That combined with a rising tide of nationalism in the country and the obvious injustices he witnessed at first hand of widespread poverty, of tenant farmers and their ongoing battles with landlords, often absentee landowners that were unseen except for their ever-present and often hated agents, shaped the character of the young Thomas Ashe.

But his love of sport, music and Irish culture in all its multi-layered facets gave Thomas Ashe a rounding and a grounding influence which he carried with him in 1908 to his new home in Fingal. Along the way he was politicised further through his work with the Gaelic League, the Irish National Teachers Organisation (INTO) and his many contacts in the trade union movement. It came as no surprise that Ashe was a vocal supporter of Jim Larkin and a close friend of James Connolly during the 1913 general lockout.

Ashe’s Fingal years read like a blueprint for a political activist intent on bringing about change based on principles of genuine freedom and human rights, but his modus operandi was more of a political activist than an active politician. The Gaelic League recognised his organisational and communicative skills when they sent him to America for eight months to raise funds from February to September 1914. His politicisation continued with contacts with activists such as the old Fenian John Devoy and with Roger Casement.

On his return to Ireland he threw himself into the recruitment and military training of young men in the Fingal area. Every layer of his character was to come together and be put to work in preparation for the approaching rebellion. His daily involvement in the GAA hurling and football club, his work for the Gaelic League, his setting up of the Black Raven Pipe Band, all were turned into fertile recruiting ground for the Fifth Battalion of the Fingal Volunteers. Ashe was pivotal to this build-up and preparation for what in effect was to culminate in a declaration of war against the British Empire. He quietly put in place a system among the Fingal Volunteers to save money each week to buy guns and ammunition. By the beginning of 1916 every member of the Fifth Battalion had a firearm of some sort.

Ashe’s position as head teacher in Corduff gave him a standing in the community which he was uniquely qualified to build on. He had very definite views on the part the Irish language and culture should play in the educational system and how it could be the means to unite the people of the country in the campaign for freedom.

Thomas Ashe was considered ahead of his time in his teaching methods and approach to education. Besides teaching the curriculum subjects as laid down by the Department of Education Ashe concentrated young minds on Irish culture, on the Irish language, on history, music and song, subjects that Corduff has always been proud to continue to this day. He had a very rounded approach to primary education, wanting to start young minds out in world not just with a knowledge of academic subjects but also with a broad base of social skills. For many of these children, particularly from poorer rural backgrounds, primary school education would be not just the start of their education but the only formal education they would receive in life. Ashe fostered a love of sport, he was a poet, a keen painter and an Irish language activist.

Thomas Ashe took a special interest in children with any kind of physical, mental or phycological disability who at the time could easily slip through the cracks in the system and fail to get a proper education.

Kitty Kelly was a former pupil of Corduff national school who had a lot to be thankful to Thomas Ashe for. Kitty was struck down by polio at four years of age around the same time that Ashe started as principle teacher in Corduff in 1908. One of my first memories of Kitty was seeing her sprawled out on the ground along the roadside one summers day beside her empty wheelchair. When I stopped and went to her assistance I discovered she had just dropped out of her wheelchair, had spread herself across a flowerbed and was happily weeding away.

When Kitty contracted Polio she spent a year in Temple Street hospital before being sent home. In a newspaper article in 1985 she recalled how her mother was wondering what was going to happen to her. “She thought I would never be able to go to school or read or write” But Thomas Ashe had no hesitation in making sure that Kitty would receive her precious education. In those years it was up to the teacher to decide if disabled children would be educated or not. Kitty was lucky to meet with another simple kindness which made her schooldays some of the happiest days of her life.

Old Mr Maxwell, a local protestant farmer, was delighted when he found out that she had been accepted into school. “He sent me over an old-fashioned bath chair- literally a basket with wheels on it- so that I could be wheeled to school by my brothers. They brought me every day to school and lifted me inside. I would sit on a seat near the turf fire when the weather was cold. On the way home they often pushed me hard to the top of the hill and let me roll to the bottom, it was a wonder I was not killed,” she remembered.

Mary Monk’s last recorded memory of Ashe was in Corduff School on the day of the Easter holidays in1916 when Ashe picked all the flowers in the school garden, handed them to Mary Monks and asked her to put them on the alter in front of the blessed sacrament on the following day – Holy Thursday.

It should be noted that this fervent and secret nationalist military preparation in the years leading up to the 1916 rebellion would not have received universal acceptance among the local population. There were parents who worried about what their sons and daughters were letting themselves in for. Local politics and personalities were still important. In Lusk there were two competing factions within the volunteers. One was led by local farmer John Rooney who co-founded the Black Raven Pipe band along with Thomas Ashe. A rival Volunteer faction were led by two other prominent families, Taylors and Murtaghs. Both groups paraded separately to Howth on the day of the gunrunning but neither company got any rifles and were told by some of the executive members of the Volunteers that they would not get any until they reconciled their differences and joined together. The Taylor Murtagh group, finally split to the John Redmond pro-British war effort while the John Rooney group threw themselves into the nationalist Easter rebellion.

Easter in Ireland always carried strange connotations of war and death as well as life and rebirth. On Good Friday 1014, before the battle of Clontarf, Brian Boru stood before his troops with a crucifix in one hands and a sword in the other. He is reputed to have said to them “ May the Almighty God, through his great mercy, give you strength and courage this day to put an end forever to their (the Danes) tyranny in Ireland.

Nine hundred years later, on Holy Thursday 1916, Thomas Ashe conjured up his ghost when he said “Should the fight begin on Good Friday, we will surely win, for we will have Brian Boru with us.

But factors outside of Ashe’s or other Republican leaders control were to fatally change the course of the 1916 Easter rebellion. In a lengthy editorial in the Evening Herald of 1st January 1917, writers looked back on the historic events in Ireland of the previous year.

“Late on Holy Thursday evening Sir Roger Casement was put ashore from a German submarine at a wild spot on the Kerry coast. Next morning he was in the hands of the police on his way to the Tower of London. On Holy Saturday night Eoin McNeill issued an order countering a general muster of the Irish Volunteers arranged for Easter Sunday. That order was obeyed so far as the Sunday was concerned but early on the following day armed battalions of the Volunteers and the Citizen’s army had taken possession of the General Post Office, the Four Courts, Stephens Green, the College of Surgeons, the Union Workhouses and other public buildings.

“They posted themselves in houses commanding the main thoroughfares and flung up barricades at the principle entrances to the city. Dublin was garrisoned by only a handful of troops at that moment, and this fact, together with the absence at Fairyhouse Races of many of the commanding military officers, gave the revolutionists time to consolidate their positions, to proclaim an Irish Republic, even to strike a Republican postage stamp, and to print a Republican newspaper. But the triumph of their colours was short-lived, for as soon as the authorities realised what they were up against, troops poured into Dublin from Belfast, from the Curragh and from England, a gunboat ran up the Liffey and bombarded the rebel headquarters, a cordon of soldiers was stretched round the city and martial law was proclaimed. Sir John Maxwell, fresh from conquests in the deserts of Africa was given plenary powers to deal with the Irish situation.

“He dealt with it so effectively, indeed that by the following Monday the rebellion was a thing of the past. And those of its leaders who had not been fighting together with the rank and file of the rebel army, were prisoners in the hands of the military. Fifteen of the imprisoned leaders were court martialled and shot, many others were condemned to varying terms of penal servitude, while several hundreds of the rank and file of the insurgents, together with a number of others who had neither hand act or part in the rebellion, were “rounded up” and deported to internment camps across the Channel, from which after eight dreary months confinement they have just been released. “

From Easter Monday until the following Saturday Thomas Ashe commanded the Fifth Battalion of the Fingal Volunteers and carried out to the letter his assigned task of disrupting and destroying enemy communications in North Co. Dublin. By Thursday Ashe and his men virtually controlled the whole Fingal area. On Friday they pulled off the biggest success of their campaign by capturing the RIC barracks in Ashbourne so that British reinforcements could not reach Dublin from that direction.

Eleven policemen were killed in the fierce fighting and between 15 and 20 were injured. Two unfortunate commercial travellers, John Hogan and JJ Carroll who just happened to be driving along the Ashbourne Road, were caught in the crossfire and killed.

John Crenigan, aged 21 from Roganstown Swords was also killed during the battle. He worked in the Dublin Tramway Company and was a member of the Swords Company of the Irish Volunteers. Tommy Rafferty, aged 19 from Lusk was fatally wounded and died shortly afterwards in a nearby cottage. Ironically he would not normally have been able to join in the military manoeuvres as he was employed on the British government Remount Farm in Lusk.

Despite the casualties suffered in the fighting, Thomas Ashe’s Fingal Brigade was jubilant at their success by Friday evening. Then on Saturday morning they received the crushing news that the Republican forces in Dublin city had surrendered, along with an order from Padraig Pearce to lay down their arms.

From a military standpoint Fingal could be very proud of what Thomas Ashe and a small group of volunteers had achieved. From a judicial viewpoint the British Government under Prime Minister Herbert Asquith deemed Thomas Ashe to have committed treason against the state. On May 11th 1916 he was sentenced to death along with Eamon De Valera, which was later commuted to penal servitude for life. He served time in Mountjoy, Dartmoor and Lewis Prison near Brighton before being released as part of a general amnesty in June of 1917. Two months later he was rearrested and charged with “causing disaffection among the civilian population,” a charge based on a speech he made at a political rally. He was found guilty and sentenced to two years hard labour with one year remitted.

Less than a month later Thomas Ashe died in the Mater Hospital as the direct result of forced feeding, after he went on hunger strike in Mountjoy Jail in a protest against being treated as a common criminal instead of as a political prisoner.

On November 1st 1917, In Dublin Castle at the summing up of an eleven day inquest on the death of Thomas Ashe, Timothy Michael Healy, the lawyer for the Ashe next of kin, , addressed the jury. “Thomas Ashe is dead. Other nations will read about it in times to come, they will be heartened by the story of this humble, uncomplaining schoolmaster, who stood up to tyranny. It is for you the jury here and now to appraise the blame as to why this man met his untimely end. It is for you to so frame your verdict that people may know that this man was no suicide. Thomas Ashe loved life and that life was brutally taken from him. If you find in accordance with those facts then his death will not have been a complete waste.”

Historians have now had the luxury of 100 years to ponder and draw their own conclusions. In 1995 I wrote a play about the inquest on the death of Thomas Ashe called The Legacy of Ashbourne. Corduff National school staged it to raise funds at the time. In my play I suggested that Thomas Ashe had been maltreated and died because of the authorities’ neglect and their disdain for what happened at the Battle of Ashbourne.

The verdict of the inquest was a fair and damning indictment of Dublin Castles failings.

We find that the deceased Thomas Ashe, according to the medical evidence of Professor McWeeney, Sir Arthur Chase and Sir Thomas Myles, died of heart failure and congestion of the lungs on September 25th and that his death was caused by the punishment of taking away his bed, bedding and boots, and being left to lie on the cold floor for fifty hours, and then being subjected to forcible feeding in his weak condition after a hunger strike of five or six days.

We censure the Castle authorities for not having acted promptly, especially when the grave condition of the deceased and other prisoners was brought to their notice on the previous Saturday by the Lord Mayor and Sir John Irwin; and find that the hunger strike was adopted against their being treated as criminals after they demanded to be treated as political prisoners. We condemn forcible or mechanical feeding as an inhuman and dangerous operation and say it should be discontinued.

We find that the assistant doctor who was called in, Dr Henry Lowe, having had no previous practise in such operations, administered forcible feeding unskilfully; and that the taking away of the deceased bed, bedding and boots was an unfeeling and barbarous act.

And we censure the Deputy Governor for violating the prison rules and inflicting punishment which he had no power to do. We infer that he was acting under instructions from the Prison Board at the Castle, which refused to give evidence and documents asked for.

We tender our sympathy to the relatives of the deceased in this sad and tragic occurrence.

But the legacy that Thomas Ashe left to Fingal, to Kerry, to Ireland and the world was a shining example of personal sacrifice and political courage. This “humble, uncomplaining schoolmaster” deserves a permanent place of honour in our memory and in our history books.

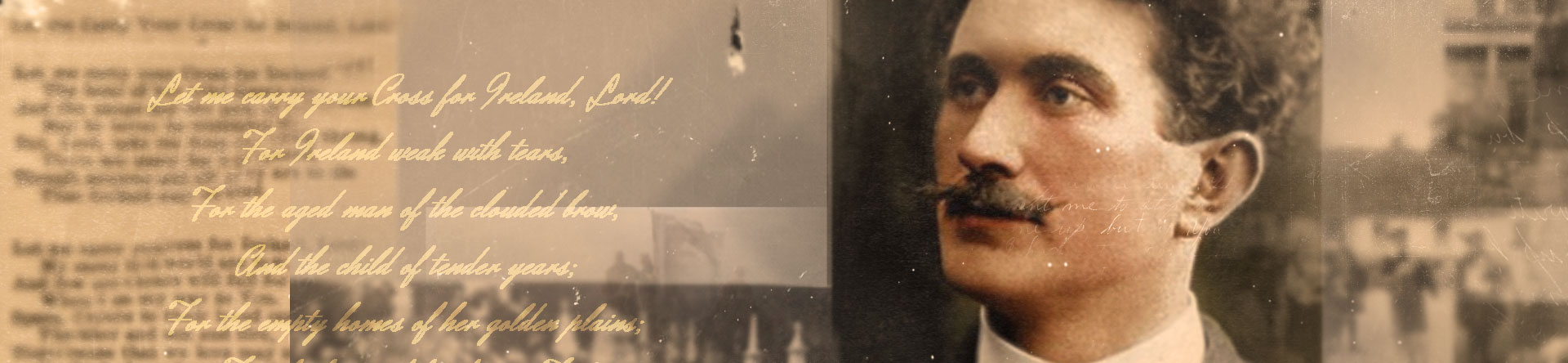

The words of his poem “Let me Carry your Cross for Ireland Lord” are a fitting epitaph for this great Irish Patriot.

“Let me Carry your Cross for Ireland Lord”

Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord !

The hour of her trial draws near,

And the pangs and the pains of the sacrifice

May be borne by comrades dear.

But, Lord, take me from the offering throng,

There are many far less prepared,

Though anxious and all as they are to die

That Ireland may be spared.

Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord !

My cares in this world are few,

And few are the tears will fall for me

When I go on my way for you.

Spare, oh ! spare to their loved ones dear

The brother and son and sire,

That the cause we love may never die

In the land of our heart’s desire.

Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord !

Let me suffer the pain and the shame,

I bow my head to their rage and hate,

And I take on myself the blame.

Let them do with my body whate’re they will,

My spirit I offer to you,

That the faithful few who heard her call

May be spared to Roisin Dubh.

Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord !

For Ireland weak with tears,

For the aged man of the clouded brow;

And the child of the tender years;

For the empty homes of her golden plains;

For the hopes of her future, too !

Let me carry your cross for Ireland, Lord !

For the cause of Roisin Dubh

AIDAN ARNOLD, 7TH MARCH, 2017